Change, the only constant at the World Cup

ICC WORLD CUP 2019 SCHEDULE[1]

When the much watched and followed Tri-series in the mid-80s, was beamed to Indian TV screens, one had already got familiar with the 30-yards circle and only two fielders allowed outside. Those rules though were not followed when matches were staged outside. The 1992 World Cup though saw these rules crystallised.

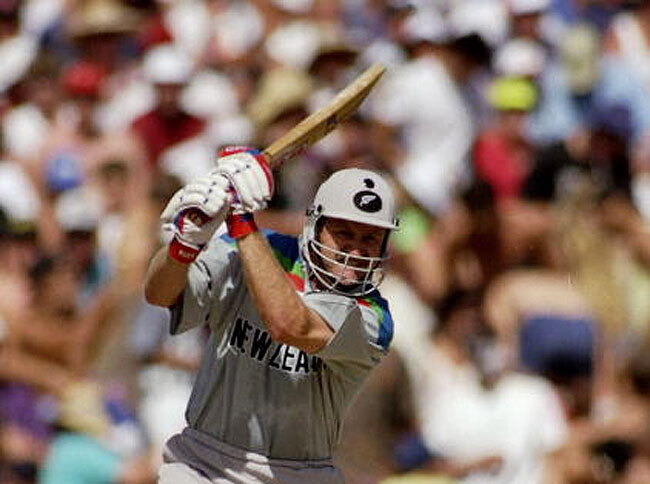

The impact: Mark Greatbatch, the Kiwi opener who was known as a strokeless wonder for his defensive game, was unchained by skipper Martin Crowe and given the license to go after the bowling in the first 15 overs. It proved a resounding success. The idea was then carried forward by Sri Lanka's dashing openers, Sanath Jayasuriya and Romesh Kaluwitharana, who were told by captain Arjuna Ranatunga[2] to attack the new ball.

The formula not only won Sri Lanka the 1996 World Cup, it also was copied by other teams and made pinch-hitting a phenomenon in the late 90s and Jayasuriya became a cult figure.

After the Asia Cup final in 1997, where Sri Lanka chased down 240 in less than 37 overs, Indian skipper Sachin Tendulkar[4] was asked what would be a safe total against Jayasuriya, "May be 1000," an exasperated Sachin said, before going on to give Jayasuriya the ultimate compliment. "I haven't seen Don Bradman[5] bat. But I have seen Sanath Jayasuriya. I haven't seen a better batsman in m y cricketing career."

A STAGNANT PERIOD TILL 2005

After the initial excitement of seeing cow boyish batting in the first 15 overs wore off, ODI cricket suffered from stagnation. The middle overs (overs number 16 to 40), became a bit boring. With the field spread out, batsmen and teams were content to just consolidate and milk the bowlers for ones and twos and chose to keep wickets in hand for the last 10 overs. With the advent of Twenty20 in 2003 and the ICC planning to stage a world event once every two years, ODIs started crying for innovation.

IMPACT: BIRTH OF THE POWERPLAY IN 2005

The term was coined by the ICC in 2005 to break up the existing pattern and introduce three sets or passages of field restrictions. Instead of two fielders being allowed outside the 30-yard circle till the 15th over, the rules stated that two fielders outside the 30-yard circle rule is mandatory only till the 10th over.

The fielding team was given the choice to then choose two sets of five overs each when an extra fielder was permitted outside the 30-yard circle.

2008: Birth of the batting powerplay: In 2008, the ICC stepped in again to make the powerplays more interesting and putting the onus on captains to think dynamically. They introduced the batting powerplay where in the batting team could decide when to use the five overs where only three fielders were permitted outside the 30-yard circle.

Impact: A lot of teams started holding on to the powerplays till the 46th over thereby giving the batsmen a free swing in the slog overs and making bowlers cannon-fodder.

2011: More changes: Sensing that bowlers were getting short-changed, the ICC tweaked the rule further and made it mandatory for all the powerplays to be used between the 16th and 40th over. In non powerplay overs, teams were allowed five fielders outside the circle.

The Decision Review System, too, was first used in the 2011 World Cup and India were one of the top beneficiaries when Sachin Tendulkar was adjudged not out by the third umpire in the semifinals against Pakistan after he was given out. Tendulkar's 85 went a long way in winning that game for India.

2012: HELLO BATSMEN, GOODBYE BOWLERS

The ICC made the ODIs more favourable to the batsmen in 2012 when they reduced the number of fielders outside the 30-yard circle in non powerplay overs to just four. Three powerplays were reduced to two with the bowling powerplay being discarded.

Impact: Lot of 300-plus scores achieved and chased down.

HELLO AGAIN, BOWLERS. SORRY ABOUT 2012

Sensing that the bowlers were getting a hiding, the ICC got together again and discarded the batting powerplay. The bowlers got more protection in the last ten overs with an extra fielder outside the circle.

Current rules about field restrictions are these:

P1: 1 to 10 overs with two fielders permitted outside the 30-yard circle.

P2: 11 to 40: Four fielders outside the 30-yard circle.

P3: 40 to 50: Five fielders allowed.

SHUT UP AND BOUNCE BABY

The one thing that excites fans on TV and those in the stadiums is a fast bowler running in, banging the ball short and bouncing the batsmen out or causing them discomfort by making them hop around. In the 1992 World Cup, the ICC had allowed one bouncer an over. Not only is it an effective dot ball, it can also be used as an attacking option, if bowled well.

In 1994, the ICC increased it to two bouncers an over. If the bowler bowled a third one over the shoulder, two penalty runs were given.

In 2001, the ICC again went back to one bouncer an over. In 2012 though, the second bouncer was allowed and penalty removed. A third bouncer is declared a no ball with a free hit.

2011, NEW BALLS PLEASE

To help the bowlers in an increasingly batsman-dominated game, the ICC thought of introducing two new balls from each end. Instead, the move spectacularly backfired. Prior to October 2011, the umpires had the option of replacing the ball at the end of the 34th over if they found it to be discoloured. It hurt the bowlers who had worked hard to keep it rough on one side to help them get reverse swing. But with two new balls at each end, reverse swing and spin was almost non-existent and it ended up in batsmen getting huge scores and hitting the ball harder and farther.

Since 2011, 300 scores of 300-plus have been registered in ODIs. Seven out of eight double centuries have been scored after the two new balls rule. 11 times 400-plus has been scored. South Africa need 22 runs from 1 ball? How many of you remember this visual on the giant scorecard of the SCG in the semifinal of the 1992 World Cup between South Africa and England. A shower that lasted 10 minutes made the target of 22 from 13 balls into 22 off 1 and knocked South Africa out. The ridiculous rain rule in the tournament meant that if rain interrupted play, the target that would be reduced would be proportional to the least profitable overs of the team that took first strike.

In 1999, the Duckworth Lewis method was introduced. According to the method, a rain interruption took into account several factors like run-rate, wickets lost and wickets in hand. Despite the occasional heartburn, it still is considered reasonably fair although experts do feel that in case of a t20 game which is reduced to six overs, the team batting second having all 10 wickets in hand does give it an unfair advantage.

2005: SUPERSUB OR SUPERDUD

Inspired by rolling substitutions in football and hockey, the ICC, in 2005, introduced the supersub rule on an experimental basis. The competing teams were allowed to name a 12th player during the toss who could substitute one of the players at any time in the game.

It produced excitement and fanfare initially and even curiosity. But it was thought to be unfair on the team losing the toss and calls were made for the team losing the toss to name the supersub after the toss.

The most famous instance of the rule being disadvantageous to the team losing the toss was noticed in the 2005 Tri-series in Zimbabwe in a match involving India and New Zealand. The Kiwis were bowled out for 215 and they had named pacer Shane Bond as their supersub. In the second innings, they replaced Nathan Astle with Bond and the fiery pacer blew India away with 6-19.

Former India pacer Agarkar, who played quite a few games during the period when the supersub rule was in effect, says: "The rule did not last long, but barring the odd occasion, we generally benefited from the rule as we did not have an all-rounder those days and we could substitute a bowler with an out and out batsman or vice-versa."

Stats indicated that 60% of the team winning the toss ended up winning the game during the supersub era. The ICC scrapped the rule in March 2006 with Australia captain Ricky Ponting's views against it being the proverbial last straw that broke the camel's back.

"I don't think there's anything lost by going back. We'll keep trying and making the best of it, but I'd like to see us going back to 11 against 11 for the World Cup."

[7][8][9]

References

- ^ ICC WORLD CUP 2019 SCHEDULE (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Arjuna Ranatunga (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Mark Greatbatch (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Sachin Tendulkar (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Don Bradman (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Ian Bell (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Shane Bond (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Nathan Astle (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

- ^ Ricky Ponting (timesofindia.indiatimes.com)

from Sports News: Cricket News, Latest updates on Tennis, Football, Badminton, WWE Results & more http://bit.ly/2XiVj6I

Post a Comment